Travel Tips

Watching the Locals

JAPAN

10/14/20255 min read

It's summer and it seems to rain every morning here. It’s not a cold rain but, rather warm and humid. It seems to start early and be finished by noon or early afternoon. That’s why the grass is green and there’s no sprinklers in the yard. It’s either raining or just misty. I have seen some Obāsan (おばあさん a general term for older women) watering potted plants or small squares of garden with a watering can or hose that they unroll and when finished roll back up. I’ve looked and have yet to see a sprinkler.

We finished breakfast at the hotel. Beef tongue yogurt, rice and miso. Breakfast is healthy and basic. I still don’t like eating the gyutan (beef tongue). It takes a lot of chewing.

We went back to our rooms to pack. There are 4 of us; my wife, Mary, my daughter Reaghan, my son Liam and myself. Liam and I shared one room and across the hall Mary and Reaghan shared a room. The general hotel room in Japan is smaller than you may be used to. It’s tough to find a room big enough for four adults.

Even outside of Tokyo or Osaka in the rural areas, Japanese hotel rooms are surprisingly small compared to Western standards. Excellent observation — and you’re right: even outside Tokyo or Osaka, Japanese hotel rooms can still feel surprisingly small compared to Western standards. The reasons shift a bit in rural areas, but the same cultural logic still applies. Even in the countryside, where land is cheaper, Japanese hotels often follow the same national design norms that guests expect everywhere: compact, efficient, and tidy. The “small but sufficient” model is so culturally ingrained that most domestic travelers wouldn’t demand a large room. Too much unused space is wasteful or even uncomfortable.

In rural areas, hotels often cater to business travelers and domestic tourists who spend their days sightseeing or bathing in onsen, not lounging in rooms. The room is meant for sleeping and bathing, not long stays.

Also in rural areas, operating costs (labor, utilities, cleaning time) are a concern and scale with room size. Smaller rooms allow for faster cleaning turnaround, lower heating/cooling costs and more guests per floor

For a business hotel near a train station, that’s more profitable and sustainable, especially during off-season months when occupancy fluctuates.

So, the small room scenario works because Mary and Reaghan do not snore. Liam and I can wake the dead, so it’s better for a good nights sleep. Today’s travel tip is you will have a hard time finding a large hotel room. If you want a large room go with airbnb or a ryokan.

The rain had stopped by time we finished packing and we had to cross the street to the train station. The last train for Nagoya leaves Shiroichi Zao at 10:28 a.m. and when they say it leaves at a certain time, it will. The trains are so on schedule that you can set a watch by them. If they are late it is unthinkable and usually caused by something unavoidable.

On the platform we huddled around our boarding position or boarding point (jōsha ichi じょうしゃいち,) the number painted on the platform. We waited, knowing that our train would be on time. And it was.

When the train came to a stop . the riders still waited patiently. There were two neat lines for each door. At each boarding point, there are two parallel lines painted on the ground — one for each side of the door. When the doors opened the passengers exited first through the middle. The locals that were waiting bowed slightly and waited until everyone had gotten off. After the last person disembarked our boarding began alternating sides efficiently , this is called 整列乗車 (seiretsu jōsha) or “boarding in orderly formation.”

Travel tip two; always watch what the locals do. If they bow at those getting off or if they bow at the engineer you should bow as well. It’s a respectable thing and it will go a long way. Use your everyday bow (会釈 – eshaku). The bow is about 15 degrees with a straight back and eyes downward. This is the “thank you” or “good morning” bow you’ll do most often as a traveler.

Everybody bowed, so we bowed and we boarded, found our seats and dug in for a quiet, peaceful, restful 4 hour ride to Nagoya. On a local or express train the ride would be about 14 hours and not nearly as comfortable.

Travel Tip #1: You’ll have a hard time finding a large hotel room in Japan. If you want more space, go with an Airbnb or a ryokan.

The Ritual of the Platform

By the time we finished packing, the rain had stopped. We crossed the street to the station, where the last train for Nagoya departs Shiroishi-Zao at 10:28 a.m. — and when they say 10:28, they mean it.

On the platform, we huddled around our boarding point (jōsha ichi, 乗車位置)—a number painted neatly on the ground. At each door, two parallel lines mark where passengers should queue. When the train arrived, everyone waited patiently. Riders exited first through the middle, while those waiting bowed slightly and stepped aside. Only after the last passenger had disembarked did the boarding begin—each side alternating, efficiently, silently.

This is called 整列乗車 (seiretsu jōsha), or “boarding in orderly formation.” It’s a small, elegant ritual that says so much about Japan: even the act of getting on a train feels like a quiet ceremony.

Travel Tip #2: Watch what the locals do. If they bow to passengers getting off—or even to the engineer—bow too. A simple eshaku (会釈) bow, about 15 degrees, with your back straight and eyes lowered, is a traveler’s best “thank you.”

Everyone bowed, so we bowed too. Then we boarded, found our seats, and settled in for a quiet, peaceful four-hour ride to Nagoya. On a local or express train, the same trip would take nearly fourteen hours—and be nowhere near as comfortable.

Arrival in Nagoya

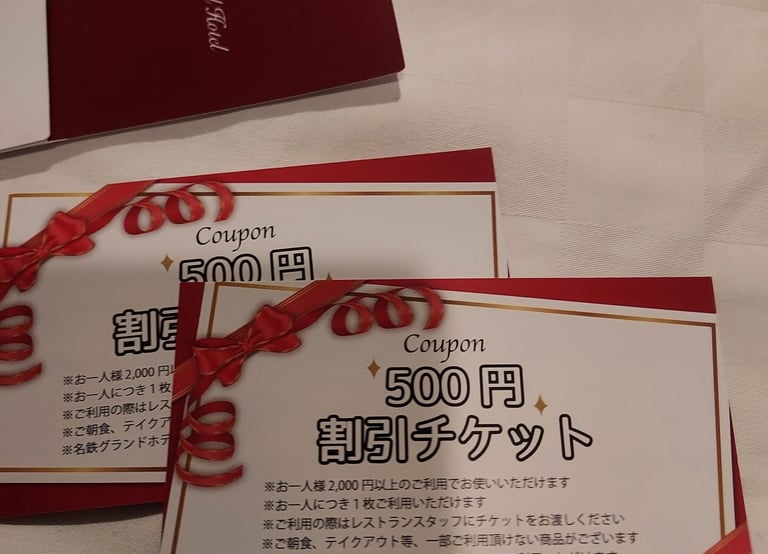

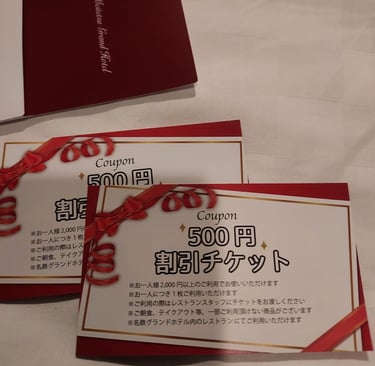

When we arrived in Nagoya, night had already fallen and rain shimmered on the station lights. We found our hotel easily — the Meitetsu Grand Hotel, just steps from the platforms. It’s an elegant building, and we felt the excitement of being one stop away from one of our main destinations: Sekigahara, the battlefield that decided Japan’s fate.

The rooms, again, were small — but familiar now. Liam and I shared one, just as before. We had brought along his favorite stuffed animal, Paco, who once resembled a collie but now looks more like a well-worn beach towel. Paco has traveled the world with my kids. Today, he lives in Tokyo with my son, standing guard over the streets of Ōta City—just as he did that night in our little room in Nagoya.

Next Stop: Where History Turned

Tomorrow we head west, to Sekigahara, the quiet valley where Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory in 1600 united Japan and began 250 years of peace. From the misty mornings in Shiroishi to the steady rhythm of the bullet train, the journey already feels like traveling through time — from the green rain of the north to the still fields where history once thundered.